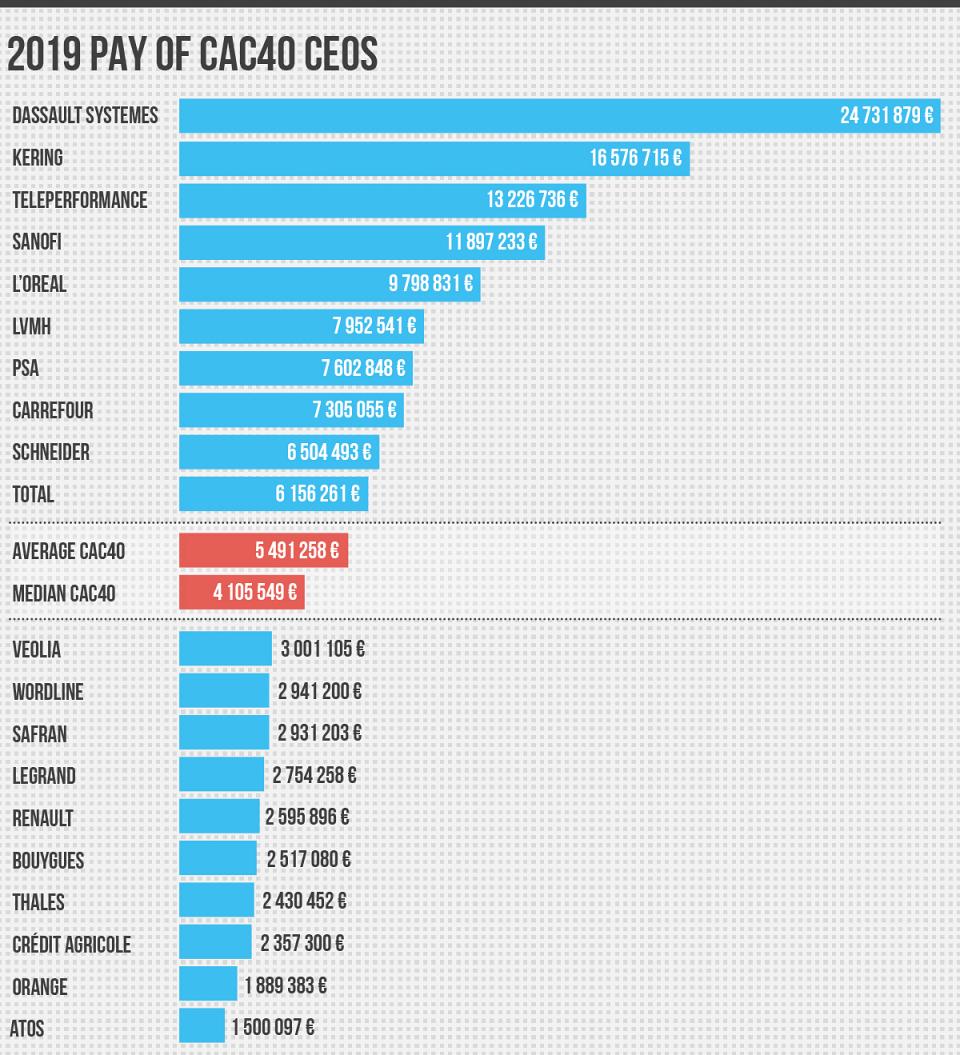

The 2019 financial year was another lucrative one for France’s corporate elite, with an average annual income of 5.49 million euros for the CEOs of CAC40 companies– three hundred times more than a minimum wage earner. The bigwigs at Kering and Dassault Systèmes feature again among the top earners, while Teleperformance CEO follows close behind.

The average annual income of France’s top executives was 5,491,258 euros in 2019, up 0.8% compared with 2018. This means that, on the 2nd of January at 5:12 am, the CEOs of CAC40 companies will have already made what a minimum wage earner makes in a whole year. By the end of the year, they will have made three hundred times this amount.

This figure, however, is just an average, with some pay cheques reaching astronomical amounts. Dassault Systèmes CEO Bernard Charlès (24.7 million euros) and Kering CEO François-Henri Pinault (16.6 million) feature again at the top of the list, as they did in 2018, both recipients of very generous “bonuses”. It would take a minimum wage earner three years and eight months to earn what Bernard Charlès earns in a day, and two and half years for them to make what François-Henri Pinault makes in a day.

In third position is Teleperformance CEO Daniel Julien (13.2 million euros) whose company entered the CAC40 index in 2020. He is followed by Olivier Brandicourt and Paul Hudson of Sanofi (11.9 million), L’Oréal CEO Jean-Paul Agon (9.8 million) and Bernard Arnault of LVMH (7.95 million).

At the other end of the spectrum are the Atos CEOs who made “only” 1.5 million euros in 2019, partly due to Thierry Breton handing over the reins to Elie Girard. The CEO of French telecommunications company Orange, Stéphane Richard, is, as he likes to gripe, frequently at the bottom of the list due to the fact that the French state is a major shareholder, nevertheless earning a decent 1.88 million. The French state also has stock in Thales, but CEO Patrice Caine still came away with 2.43 million euros in 2019.

CEO pay is designed to align their interests with those of shareholders

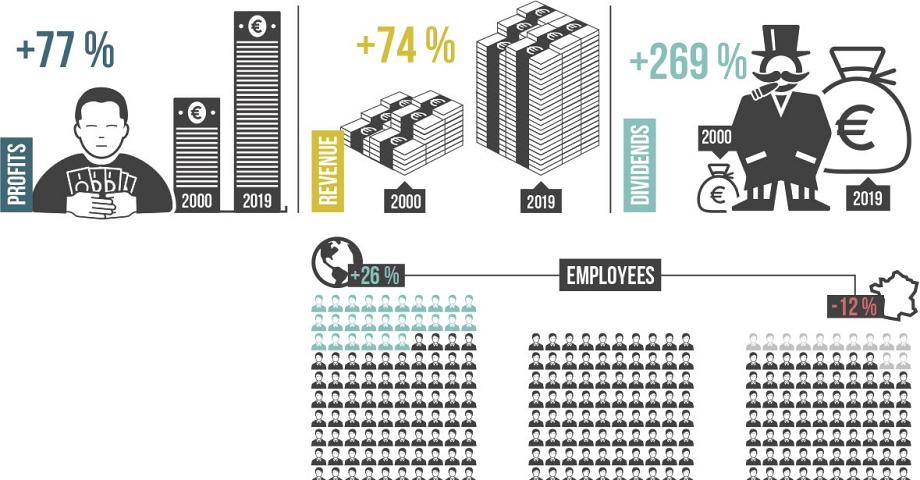

It is no coincidence that dividend payouts and CEO compensation have both been sharply rising for a number of years. The amount that CAC 40 senior executives are paid is now directly related to shareholder satisfaction.

Several decades ago, the CEO of a major corporation would typically get their basic pay, plus a variable pay which would fluctuate depending whether specific business targets were met. Their job (at least, in theory) was to protect the interests and overall long-term health of the company, which included the interests and loyalty of their employees, shielding both the company and its employees from rapacious shareholders or those looking to make a quick buck. They would receive a very comfortable but not quite extravagant salary. In 2000 still, the entire executive committee of French retail giant Carrefour, i.e. eleven people, received a total of 6.11 million euros – quite a bit less than the seven million paid out to the company’s CEO Alexandre Bompard in 2019.

Nowadays the sums pocketed by senior executives have little to do with their company’s performance, and even less to do with what regular workers are earning. They do, however, have something to do with the sums being paid out to shareholders in dividends and buy-backs. Since 2000, shareholder pay-outs and executive salaries have increased by 70% and 60% respectively, while the average salary of an average corporate employee has increased just 20% – three times less than their bosses. [1]

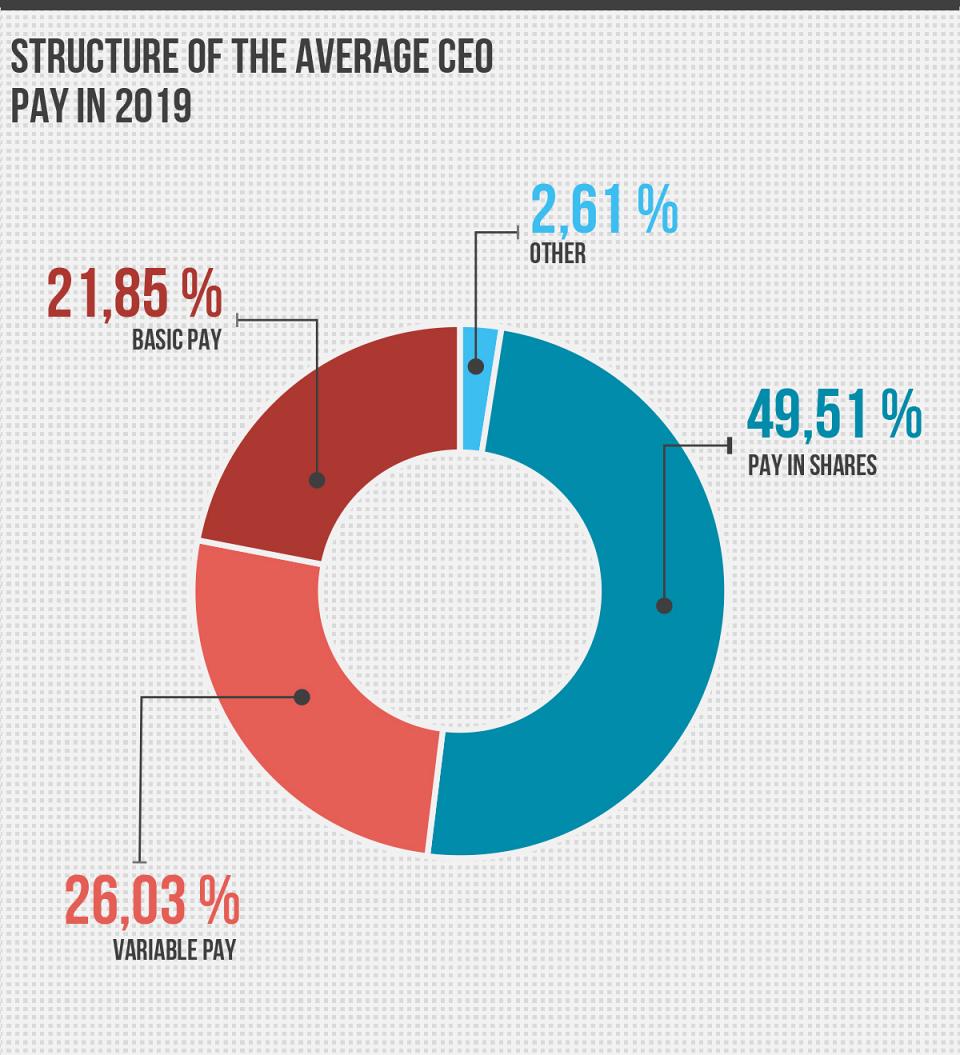

So what happened? Deregulated financial markets and neoliberal economic doctrines radically changed the way CEOs are compensated. A CEO’s “actual” salary – their base pay – now represents less than a quarter of the amount they receive (21% in average for CAC40 CEOs in 2019). Their variable compensation – based on financial targets and occasionally societal and environmental objectives – represents 26%. Stock awards, however, represent, on average, more than half of the compensation that a corporate CEO receives. Therefore, three quarters of their compensation is directly or closely related to the share price of their company. This ensures they will always keep shareholders’ interests high on their list of priorities.

The hefty pay packets of CAC40 CEOs are directly related to the hefty dividends being paid out to shareholders. For the “two record-holders”, Dassault Systèmes and Kering, stock awards represent more than 80% of compensation (and 74% and 64% respectively for the CEOs of Sanofi and Teleperformance). Three firms, however, do not currently pay their CEOs stock awards: Atos due to the current handover; and Hermès and Bouygues, because their CEOs are already dominant shareholders. “Martin Bouygues does not receive long-term variable remuneration given his personal circumstances, which already guarantee that his interests are aligned with those of the shareholders,” explains the construction group. [2] Other major shareholder-CEOs on the CAC40, such as Bernard Arnault (LVMH) and François-Henri Pinault (Kering), are quite happy to accept stock awards.

Dividends: the cherry on top

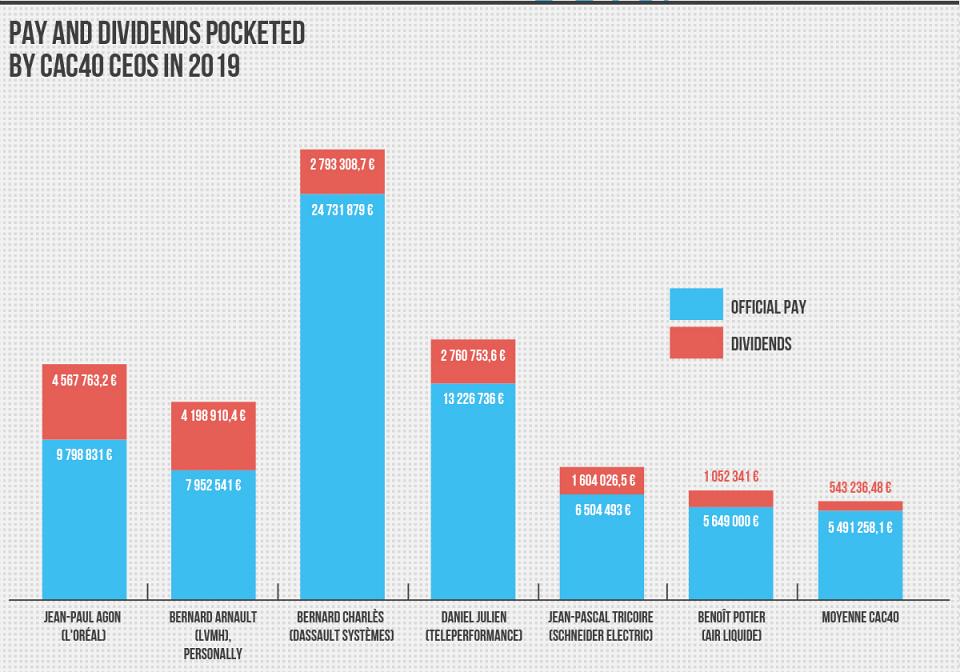

In addition, there is usually a hidden bonus. The amount earned by the CEOs doesn’t stop at their “official” pay. As virtually all of them have shares in the companies they manage, they are also entitled to – surprise, surprise – dividend pay-outs. The circle is complete.

Even when CEOs are not already the majority shareholders of their company via a family holding company (LVMH, Kering, Bouygues, ArcelorMittal, to name a few), the additional compensation they receive can be very sizeable. L’Oréal CEO Jean-Paul Agon, who will pocket a tidy 4.57 million euros in dividends for the 2019 financial year, is a case in point. This “bonus” will raise his official salary of 9.8 million euros to an unofficial total of 14.4 million for the 2019 financial year. The CEOs of Dassault Systèmes and Teleperformance will each receive 2.8 million euros in dividends on top of the handsome sum they already take away. And CEOs of Schneider Electric and Air Liquide will be paid an additional 1.6 and 1 million euros respectively.

For the 2019 financial year, a CEO of a CAC 40 company will get an average of 543,236 euros in dividends – thirty times more than the annual income of a minimum wage earner – in addition to their official pay – an average of 5.49 million euros. And this figure could have been significantly higher if it were not for COVID-19 and its impact on dividend payouts.

Lies about the real pay gap

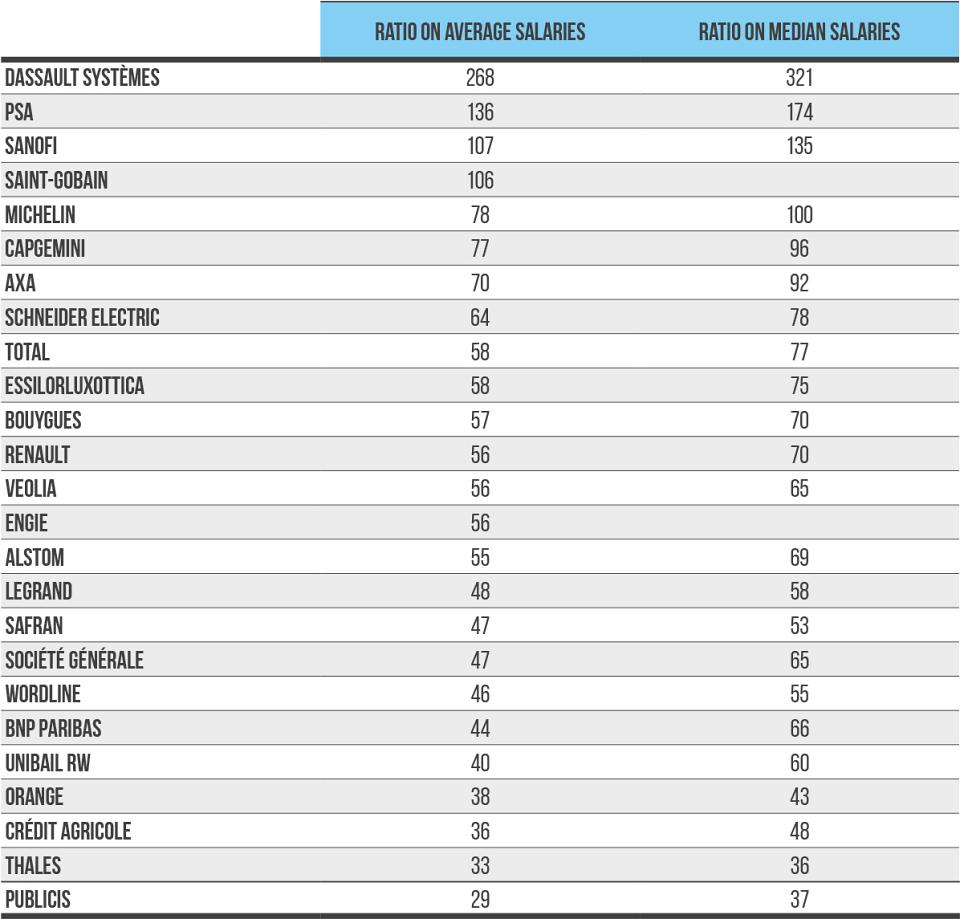

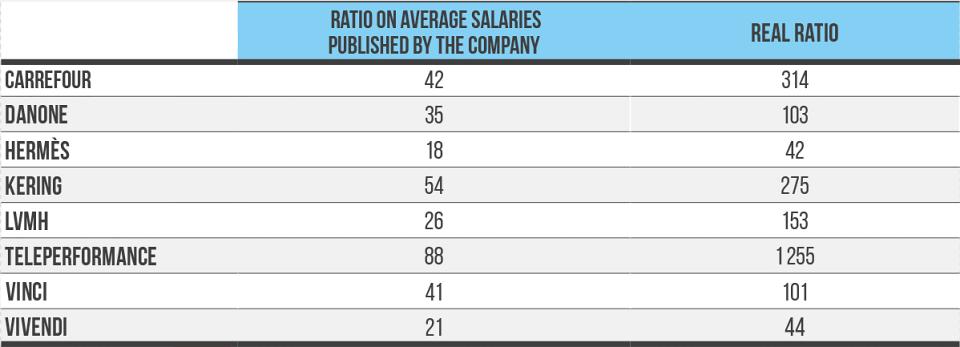

This year, companies on the CAC 40 had to disclose, for the first time, a “CEO to worker pay ratio”, comparing the compensation of employees with that of their CEO. But the methods adopted by most companies to calculate this ratio gives a very distorted picture of the situation.

This year, companies on the CAC 40 are required to disclose a “CEO to worker pay ratio”, comparing the compensation of the top executives to the average and median income of the company’s employees. They must also disclose year-by-year changes in compensation. On paper, this looks like real progress. The problem lies in how the ratio is being calculated.

Many companies on the CAC 40 have managed to find a way to comply with the provisions of the law while getting around what the law is actually asking of them. They have included only the employees of the parent company in their calculations, i.e., the legal structure that oversees the group’s companies and subsidiaries. In most cases, these parent companies only have a few dozen employees, sometimes even less, and they are often amongst the highest earners within the groups. The pay ratio is based on a tiny fraction of the workforce in which the well-paid are over-represented, thus providing a skewed representation of reality.

The most extreme example is undoubtedly that of Teleperformance. Including all its subsidiaries, the company has a total of 330,000 employees, and yet its parent company has only 41. This means that, according to the company’s calculations, the average pay ratio is “only” 88-to-1 whereas the real figure is actually much higher (see below). A dozen other firms on the French index have used the same method to fudge their figures. These include Air Liquide, Carrefour, Danone, Hermès, Kering, L’Oréal, LVMH, Pernod-Ricard, Saint-Gobain, Vinci and Vivendi. Unsurprisingly, many of these happen to be companies that don’t rate highly when it comes to pay equality in the workplace.

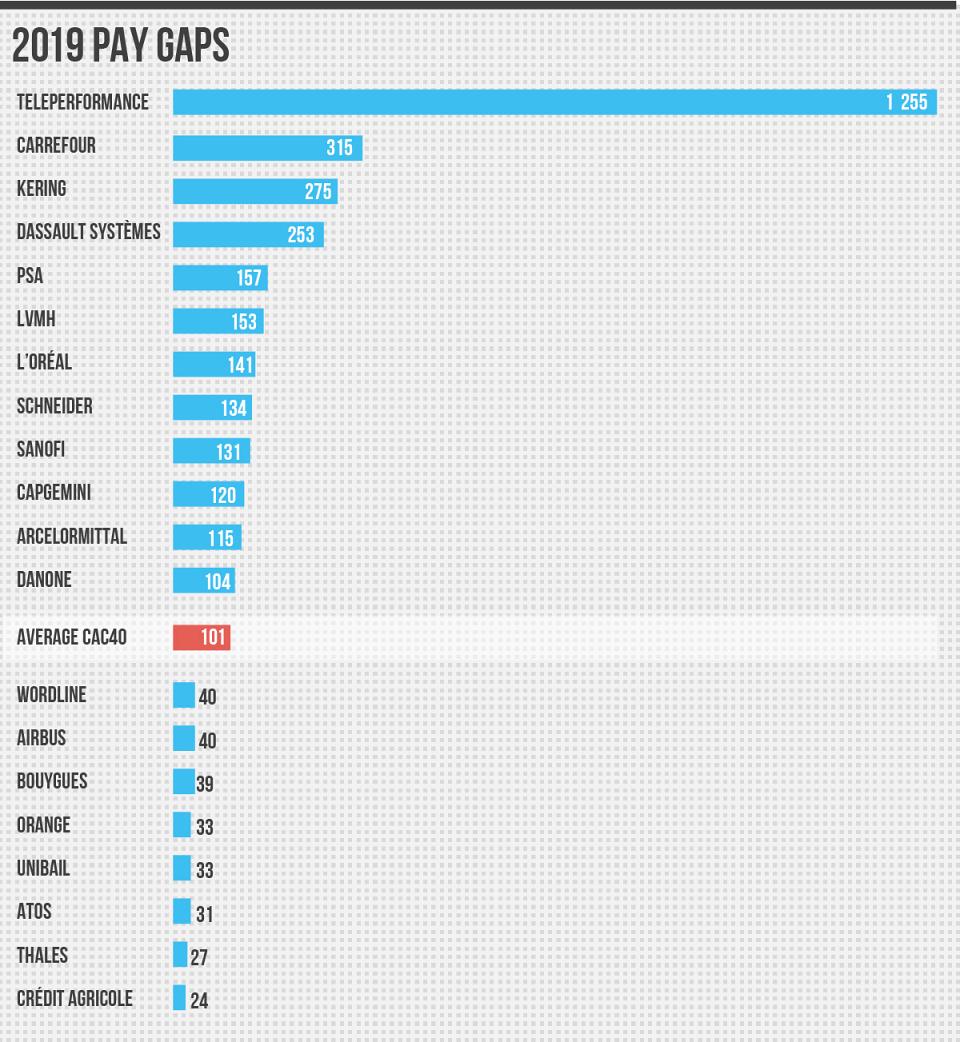

Other CAC40 companies have disclosed more accurate ratios, based on a wider sample of their employees (although its remains generally restricted to those based in France). The following table shows the published pay ratios that were calculated over a sufficiently large sample of employees. The higher these ratios are, the more unequal compensation is within companies. These pay ratios are systematically higher for median salaries than for average salaries, which suggests that it is not only the CEO who is paid disproportionately, but that significant pay inequality exists within the groups themselves.

A more accurate picture

To get a better idea of the real pay gap between corporate executives and workers, we used another indicator: average annual spending per employee. This indicator is based on the only data that all companies systematically and consistently publish: employee numbers and labour costs. It is not as precise as the CEO to worker pay ratio (when calculated correctly) because there is no way of knowing whether employees are based in France or not, or whether they are full-time or part-time employees. It can only give an average value, not a median value, which would be more useful in terms of measuring the real state of pay inequality. Nevertheless, it gives a rough idea of the situation.

In 2019, average annual labour costs per employee for companies on the CAC 40 stood at 54,168 euros. These figures are down from 2018 when average spending was 57,300 euros. This represents a pay ratio of around 101-to-1, against the average CEO compensation (excluding dividends) of 5.49 million euros. In other words, a corporation on the CAC40 spends, on average, 101 times more on its CEO than on an average employee – and this figure is obviously even higher for an employee at the bottom rung of the ladder.

According to this indicator, of all the companies on the CAC40, income inequality is highest (by a long shot) at Teleperformance with a pay ratio of 1,255-to-1. In other words, it would take an average worker at Teleperformance three and a half years to make as much as CEO Daniel Julien makes in a day. The company, specialised in call centres, pays its CEO an exorbitant salary (over 13 million euros) while annual labour costs per employee are very low (10,538 euros). Other big differences are due to low labour costs (Carrefour) or to high CEO compensations (Kering and Dassault Systèmes). At the other end of the spectrum, firms where income inequality is lowest are generally those where executive compensation is kept relatively in check, such as Crédit agricole and Thales, or where average labour costs per employee is high (Airbus and Unibail).

The following table shows the glaring differences between the biased CEO to worker pay ratios published by certain companies, based on the average income of parent company employees, and our own pay ratios, calculated according to method described just above.

Donate

Independent information on corporate power is critical, but is has a cost.

Donate