This article was first published as an introduction to our publication Democratic Information in an Age of Corporate Power.

It seems obvious that without information, democracy cannot exist. It’s impossible to imagine modern democracies without the free flow of ideas, without press freedom or open discussion and debate, without regulations that force political leaders to be accountable for their actions (however partial and imperfect this accountability might be in practice).

Yet we live in a time where the emergence of new forms of power – economic powers – are making their mark, and are having an increasing influence on our lives and our societies. The mounting power of transnational corporations is particularly symbolic and the most striking manifestation of this reality. Various factors have contributed to the rise of these global corporations, including the financialisation and globalisation of the economy, technological change, the hegemony of neoliberal ideology, and the relative weakening of state power (or the failure of states to fulfil their responsibilities). In a democracy, all forms of power need counter-powers – yet the forces that could potentially counterbalance the power of these corporate heavyweights (unions, public authorities and civil society) seem weaker than ever.

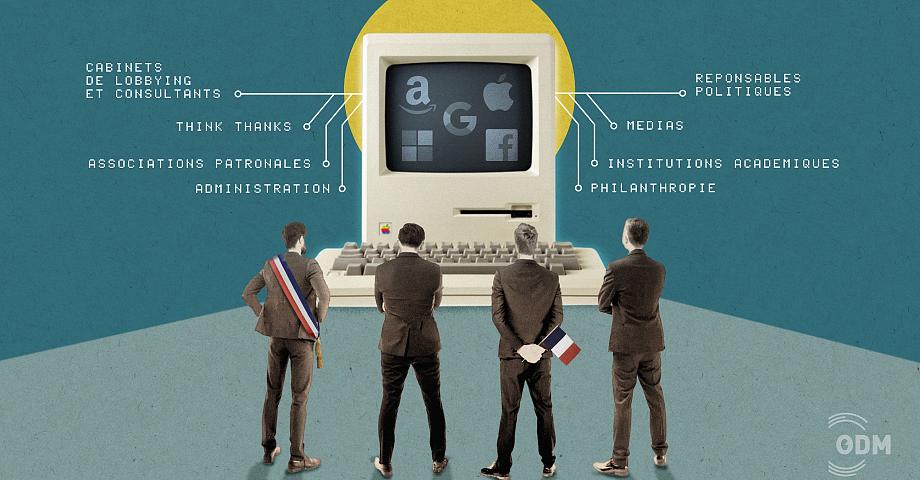

Do we have enough information to confront these new powers, which affect so many areas of our lives, and impact on so many issues of public interest, and which are so powerful and influential that they can no longer be considered as merely “economic”? Obviously not. The media are structurally geared towards political power. They tend to overlook economic power despite the fact that it is playing an increasingly decisive role in our lives. And yet the frightening reality is that these economic powers are influencing and transforming – or perverting – political power, so that decisions are no longer being made only in public assemblies but also out of the public eye, in corridors and offices where lobbying activities go on. The growing influence of corporate power can also undermine civil liberties and freedom of speech, which are the foundations of political democracy. In some countries there is even pressure on public authorities to silence those opposed to certain corporate developments.

In many ways, as we shall see below, lack of information is intrinsic to corporate power in its current form. This is why there are so many and often irrational fears and fantastical views of transnational corporations as some kind of dark force, which sometimes slide into conspiracy theories. In such a context, providing independent information on TNCs is also a way to bring back a bit of rationality into the discussion. Only anti-democratic forces, such as the far right, can thrive off the absence of information and genuine political discussion.

Too little information on TNCs despite a desperate need for it

Why is there so little relevant and democratically-useful information on TNCs given the reality of their power and how important the issues at hand are? This is due to a number of reasons:

Firstly, though their power is very real, it is not always perceived as such because it does not fit into traditional distinctions between politics and business, between public and private. As previously mentioned, this power is wielded outside of the public eye, across jurisdictions, and is often out of reach of citizen oversight and other traditional countervailing powers, making it even more difficult to grasp.

In addition, multinational corporations are by definition present in a number of countries, which are often situated at opposite ends of the globe. The language barrier and the geographical distance are two very concrete issues that contribute to making to difficult to ascertain what is happening on the ground on the other side of the world. It is often difficult even for unions working for the same corporation in different countries to communicate and share information due to constraints on time and resources. The same goes for the different local governments where they operate – and, of course, for the communities living around them. In France, we are very far from knowing the reality of what our national corporations are doing in other parts of the world. TNCs are experts at playing their own game of hide and seek.

Another issue is that information on TNCs is often extremely inaccessible due to its highly technical jargon, making it difficult for most people to get through the web of financial and stock market verbiage. This jargon only gives a very partial (in both senses of the word) picture of the corporate reality. The sad truth is that Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), with its large-scale bureaucratisation, has become just another strain of technical jargon, which hides as much as it reveals.

Furthermore, corporations always have an economic interest in information relating to their operations. They have to strike the right balance between transparency, the public interest and the commercial sensitivity of information. It’s for this reason that corporations often require their employees to sign confidentiality agreements and guarantee discretion. Since they largely dictate which information should be available to the public, they tend to take an evasive approach, saying as little as possible – particularly when it comes to sensitive subjects – and the only information they provide is filtered through their stringent communication strategies. This tendency to shy away from transparency is likely to become even more pronounced with the recently adopted EU Trade Secrets Directive.

These are the reasons that make it difficult for journalists to determine exactly what corporations are doing and to assess the impacts of their operations, especially when it comes to complex and potentially daunting issues. The major scandals that end up on the front page of newspapers represent only the tip of the iceberg. But the skimpy amount of information on corporations in the press (compared to the way they follow political leaders’ every move) is also a reflection of the fact that these newspapers are often owned by the corporations themselves. The situation is particularly caricatural in France, but it is the same in a number of other countries. And if we consider the mainstream media’s dependence on advertising (for products often sold by these same corporations) to pay the bills – we begin to get an idea of just how little investigative work there is on the corporate world, especially when we consider the extent of their influence on our lives. Thankfully, the importance of investigative journalism is now being acknowledged and positive initiatives are cropping up all over the place – with the emergence of new kinds of non-commercial, non-profit journalism.

Overview

This issue of Passerelle aims to get an overview – however incomplete and fragmentary – of these issues.

The first section deals with issues around freedom of information in an economic and corporate context, including corporate activities and their impacts. It addresses in particular the threats (both old and new) that are jeopardising freedom of information, including the recent emphasis on “trade secrets”, and also looks at the role played by journalists and the media.

The second section focuses on transparency and reporting issues – that is, the information that corporations are required (or not) to disclose to the public. These articles tend to reveal an extremely inadequate level of transparency particularly in the area of tax systems, lobbying and corporate welfare.

The third section gets into the nitty-gritty of corporate life and studies the needs and rights of employees and unions in terms of information, and how these are connected to (or disconnected from) the needs of society as a whole.

And the last section, which is also the longest and most exploratory, outlines a number of initiatives, organisations and networks that are all contributing, in different ways and from different perspectives, to producing independent information on corporations that can be wielded by society. These “information counter-powers”, although often little-known, nevertheless play a crucial role in keeping economic and corporate powers in check, ensuring that they remain subject to democratic debate. The fact that their resources are so meagre compared to those of corporations only makes their achievements even more remarkable.

Their diverse initiatives and approaches highlight the need to create new forms of collaboration and information sharing (several of which are discussed in this issue), as well as the need to define new rights and new regulations in regards to accessing economic information and independent “second opinions”.

It’s clear that we are facing a number of obstacles, as the EU leaders’ eagerness to protect “trade secrets” at all costs has made glaringly obvious. And this is just one aspect of an overall trend that exempts corporations from playing by the rules of a democracy, that allows them to operate outside of the public eye, making them almost untouchable (not so different from the private arbitration tribunals between investors and governments used for issues relating to free trade agreements such as the proposed TTIP agreement between the EU and the USA).

The issue of information, together with that of legal liability and binding rules for transnational corporations, seem to be one of the core issues integral to the fight for economic democracy – or the fight for democracy full stop. Although information may seem “immaterial” compared to the very real sanction of a judge, its importance shouldn’t be underestimated. Firstly because the “reputational risk” is extremely important for companies. There is no corporation that wishes to be accused of causing environmental damage or violating human rights – both due to the damage this would cause to their image and brand (in which lies a substantial part of their wealth), and the ensuing domino effect that would result from a “bad reputation” among investors or public authorities.

And secondly, because corporate power is always based on a certain level of information asymmetry, which ensures they are in control of the game. And so disseminating independent information also enables those who have a degree of real decision-making power that impacts upon corporations – public authorities, investors, communities, as well as corporate employees and executives – to use this power effectively, influence business practices, and refuse to accept that which is unacceptable. In the end, perhaps the most useful information on corporations is information on alternatives to corporations: examples that prove that we can do things differently, and that we don’t need them to do it.

Olivier Petitjean

—

Image : Tybo CC